A Tribute to Hank Williams 19xx-1953

In December of 1952 Hank played at a gig at the Skyline Club; it was to be his last. On his way to his next gig in Canton, Ohio, Hank died while sleeping in the back of a car at the age of 29.

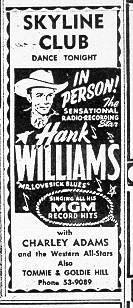

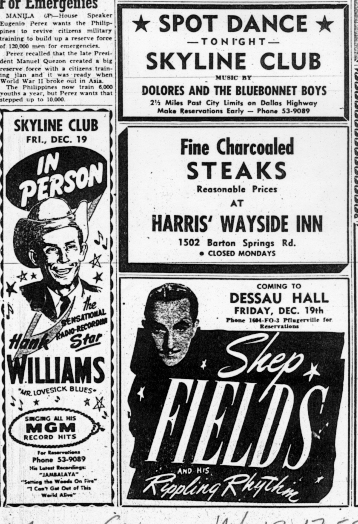

A December, 1952, Austin Newspaper Ad for Hank Williams Sr.'s Appearance at the Skyline Club

Hank Williams saved his best for last, or almost last, and Austin

was the beneficiary.

Though he would play a pickup date or two during the final weeks of

his life, his show at

the Skyline Club on what was then the northern outskirts of town

marked the end of

the final tour of his 29-year-old life. The date was Dec. 19, 1952,

and the place was

packed.

While he was still enjoying his reign as the best-selling country

artist in America, his live

performances had become increasingly chancy, due to Williams'

dependence on

alcohol, morphine shots, Dexedrine and painkilling pills, which

provided the oblivion the

spindly, sickly musician sought from spinal deterioration and

marital wounds. Those few

promoters who continued to book him -- including Austin's Warren

Stark, who owned

the Skyline and handled the rest of Williams' dates in East and

Central Texas --

knew that there was only a 50 percent chance that he'd show. And if

he showed, there

was no predicting his condition.

During the week of his Austin date, he'd already been booed off a

stage in Houston and

had canceled a show in Victoria. Earlier in the month, at a concert

in Lafayette, La.,

he'd stumbled onto the stage, snarled, ``You all paid to see ol'

Hank, didn't ya? Well,

you've seen him,'' and stalked off without singing a note.

So, there was no reason to anticipate that Williams would deliver

one of the greatest

and longest performances of his career at his final hurrah in

Austin. Yet, according to

Colin Escott's ``Hank Williams: The Biography,'' such a triumph is

exactly what

transpired. Backed by the Skyline house band and steel guitarist

Jimmy Day (the

sometime Austinite who would later play with everyone from George

Jones to Don

Walser), Williams pushed well past his typical 30-40 minute

performance to close the

joint past 1 a.m. with two full sets, singing everything he knew,

the hits more than once

or even twice. Whether or not he realized that his time was short,

he poured everything

into one long night in front of about 800 fans in a club in North

Lamar. Twelve days

later, he was dead, perhaps on New Year's Eve, discovered on New

Year's Day,

slumped and blue in the back seat of a white Cadillac on the way to

a show in Canton,

Ohio.

Even by the punk-rock standards of a Kurt Cobain, Williams' life

was a mess. But what

a glorious mess of music he left behind, a legacy exhaustively

documented through

``The Complete Hank Williams'' (Mercury), a 10-CD collection

released to

commemorate what would have been his 75th birthday today . Among

the 225 cuts are

53 previously unissued, ranging from alternate takes of classics

such as ``Lovesick

Blues'' and ``Cold, Cold Heart'' to scratchy demos from the early

'40s, when he was still

mimicking the likes of Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb while honing his

songwriting chops, to

tapes of his radio, television and concert performances to a spoken

apology delivered

before a concert that Williams was unable to make.

It also, of course, includes the entirety of his recordings for

MGM, the five-year output

that has since been memorialized as the best of country music.

During his life, few

suspected that Williams' music would prove so timeless, since it

seemed at the time

such a relic from a South that was behind the times, where so many

of Williams'

hardcore fans didn't even enjoy the conveniences of electricity and

indoor plumbing. For

all of his regional popularity, Hank was a hayseed to mainstream

America, palatable

only when a song such as ``Cold, Cold Heart'' was pasteurized by

the likes of Tony

Bennett. (One of Bennett's breakthrough hits on the pop charts, it

was promoted in the

musical trade publications with the slogan: ``Popcorn! A Top Corn

Tune Goes Pop.")

Now remembered as the greatest of country songwriters, a populist

poet, Williams

enjoyed his own commercial breakthrough with 1949's ``Lovesick

Blues,'' a show tune

(by Irving Mills) from decades earlier that he was discouraged from

recording. ``I'm So

Lonesome I Could Cry,'' Williams' favorite among his own

compositions, was relegated

to the flip side of the novelty ``My Bucket's Got a Hole in It.''

``Jambalaya'' was initially

considered another novelty, the sort of commercial trifle with the

shortest shelf life,

though it remains one of Williams' most often-recorded classics.

``Your Cheatin' Heart,''

remembered as his signature tune, wasn't even released until almost

a month after

Williams' death.

Much of Williams' most powerful material was inspired by his

combustible relationship

with ``Miss Audrey,'' to whom he was married and divorced twice,

and who gave birth to

Hank Jr. (actually Randall Hank, where Hank's given name was Hiram)

during one of

their off-again periods. By most accounts, she was even more

impossible than he was,

making Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald look like Ward and June

Cleaver by comparison.

She insisted on being part of the act, though her singing screech

was only borderline

listenable; she spent his money faster than he could make it; she

hounded him at home

and cheated on him when he was on the road, though Hank had his

indiscretions as

well.

But listening to the songs that resulted -- ``Why Don't You Love

Me,'' ``You Win Again,''

``My Love for You (Has Turned to Hate),'' ``I Just Don't Like This

Kind of Livin,''``You're

Gonna Change (Or I'm Gonna Leave),'' as well as the aforementioned

hits and

countless others -- makes it plain that the artistic dividends more

than justified the

marital misery, at least where his artistic legacy is concerned.

Such songs reinforced

his bond with his fans, for, as Escott explains, ``he made his

audience feel that ol' Hank

was truly one of them, always in the 'dawghouse,' always one step

ahead of the bill

collector."

``What always impressed me was how young he was and how old he

looked,'' said

Sammy Allred, KVET-FM's morning curmudgeon and musical comedian

with the

Geezinslaws. ``And how skinny. I was at the Coliseum when Hank

played here, two

years after 'Lovesick Blues,' 'cause I remember he said, 'I've been

living off this song for

two years.' My cousin and I used to sneak in, carrying an empty

guitar case and go

walking in through the back door. We started talking to him, and

Minnie Pearl was

there, too.

``And he said, 'Boys, why don't we walk outside and talk so Miss

Minnie can change

clothes.' Rather than saying, 'You boys got to leave,' he walked

outside with us and shot

the bull and smoked a cigarette."

Whenever musicians threatened to make his music a little too fancy

or jazzy, Williams

repeated a two-word admonition, ``Vanilla, boys.'' The

improvisatory sophistication of a

Bob Wills was not for him; he wanted his songs to retain the sturdy

simplicity of the

purest hymns or the most basic blues. Upon hearing a Hank Williams

song for the first

time, it sounded so familiar that you felt like you'd been hearing

it forever. And the title

was imprinted on your brain with every chorus.

In retrospect, it's less a tragedy that Williams died so young than

a mystery that he

managed to live so long, while compressing so much life and

accomplishment into that

span. Consider that during the final six months of his life, he was

divorced from Audrey

for the second time, had an affair with Bobbie Jett that would

spawn an illegitimate

daughter, married the 20-year-old Billie Jean Jones Eshliman before

her divorce was

final (and would start announcing his intention to divorce her

within weeks), was fired

from the Grand Ole Opry, took a leave of absence from the Louisiana

Hayride, lost his

manager and his band, saw ``Jambalaya'' top the country charts for

three months

straight and recorded ``Your Cheatin' Heart'' at his final session.

Throughout the period,

he was alternating sanitarium visits with drinking binges, while

doping himself with

painkillers that left him impotent and incontinent.

Sources:

BYLINE: Article by Don McLeese, 09-18-1998, The Austin American-Statesman, Page E1

Article by Michael Corcoran, Page 24, The Austin American-Statesman, 09-07-2000

A December, 1952, Austin Newspaper Page Displaying Music Events at the Skyline Club and at Dessau Hall